Employee theft ‘shockingly common’ at nonprofits

Boston Globe

By Todd Wallack

27 January 2018

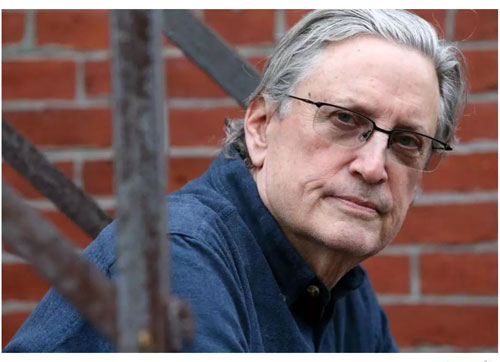

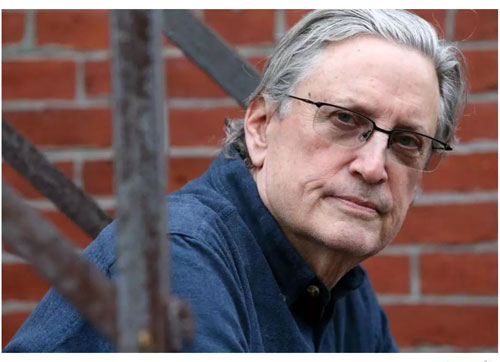

“The whole

thing has been a nightmare,” said Mark Alston-Follansbee, executive

director of the Somerville Homeless Coalition, whose former chief

operating officer is accused of embezzlement. Craig F. Walker Globe Staff

A board member for the Somerville Homeless Coalition was reviewing the

nonprofit’s annual financial documents in 2015 when he spotted

something odd. The forms said the chief operating officer, the No. 2

executive, earned $12,000 more than the organization’s top executive

the previous year. Could that really be correct, he asked?

Turns out it wasn’t a typo. It was theft.

Somerville Homeless soon discovered that the COO — who handled all the

finances — allegedly embezzled approximately $108,000 over 18 months.

The charity said he brazenly added some of the money directly into his

paycheck — where it showed up on the group’s annual financial forms —

used the organization’s credit card for personal expenses, and added

his middle-aged son to the group’s health insurance.

“The whole thing has been a nightmare,” said Mark Alston-Follansbee,

executive director of the Somerville nonprofit, which provides food,

shelter, and other assistance to about 2,000 people annually. “The

money he stole from us could have prevented 100 families from going

homeless.”

More than 1,100 tax-exempt organizations nationwide have reported

theft, embezzlement, or other major diversions of assets over the past

seven years, according to electronic filings with the Internal Revenue

Service. And experts say the total number of thefts is almost certainly

far higher, because most cases of fraud are either never detected or

reported in the digital filings.

“It’s shockingly common,” said Gerry Zack, a certified fraud examiner

who recently was named incoming chief executive of the Society of

Corporate Compliance and Ethics, a Minneapolis-based organization.

nonprofits are particularly vulnerable for a variety

of reasons: Many nonprofits are small organizations, led by people who

are passionate about their causes but may not have a background in

finance. Board members are typically volunteers, with limited time or

expertise in oversight.

To be sure, for-profit businesses are regularly victims of fraud as

well. But some say nonprofits are particularly vulnerable for a variety

of reasons: Many nonprofits are small organizations, led by people who

are passionate about their causes but may not have a background in

finance. Board members are typically volunteers, with limited time or

expertise in oversight.

Thefts, in fact, can be hard to spot. For instance, when a contribution

goes missing, the fraud may go undetected because donors generally

don’t expect anything in return for their gifts, unlike business

customers who usually complain when what they paid for never comes.

“There’s at least anecdotal evidence that would suggest nonprofits are

more susceptible to fraud than traditional for-profit companies, said

Zack, who also teaches classes for the Association of Certified Fraud

Examiners, based in Austin, Texas.

The issue is particularly relevant in Greater Boston, where so many

prominent institutions are nonprofits, including major hospitals,

universities, museums, and research organizations. More than 70

nonprofits in New England have told the IRS they were victims of

embezzlement or theft in recent years.

For instance, a bookkeeper was sentenced to two years in prison in 2016

for stealing $800,000 from the National Veterans Services Fund of

Darien, Conn., from 2009 to 2014, writing checks to herself and then

altering the ledgers to make it appear the money went to veterans.

Population and Development International, a nonprofit dedicated to

helping the rural poor in Southeast Asia, reported its then-president

diverted $950,000 for his personal use in 2012 when the group was based

in Boston. The charity said the executive promised to make full

restitution as part of a settlement, but a former director said no one

was ever prosecuted.

And a former machine shop manager at Massachusetts General Hospital in

Boston was sentenced to a year in prison in 2014 for stealing more than

$640,000, in part by ordering tools and equipment for his own use as

well as by selling leftover brass discs to scrap dealers after they

were used in radiation treatments.

The problem is national in scope, touching some of the country’s

best-known nonprofits. The American Museum of Natural History in New

York City reported it lost $2.8 million in 2015 after an employee fell

for an e-mail scam and erroneously wired the money. The museum reported

the incident to police, but the perpetrators have yet to be identified

or return the money.

The IRS asks tax-exempt organizations to disclose any significant,

unauthorized diversions of assets (usually meaning theft or

embezzlement) on a key annual filing with the agency, called a 990. The

Globe found more than 1,100 organizations across the country have

checked the box on forms filed electronically since 2011.

But the vast majority of nonprofits never even face the question. The

IRS omitted the diversion question from versions of the form filed by

foundations and most smaller organizations, while certain types of

organizations, such as churches, are not required to file at all. And

many organizations fill out paper forms, where the data are harder to

compile. Overall, fewer than 1 in 7 nonprofits file the standard 990

electronically each year.

And even organizations that file electronic 990s aren’t required to report smaller thefts.

For instance, a temporary employee was caught in 2013 embezzling

$68,000 from the Boston VA Research Institute, which supports medical

research and education in the VA Boston health care system. The

employee was sentenced to prison, but the nonprofit never reported the

incident to the IRS, citing agency guidelines that say nonprofits need

only report diversions totaling more than $250,000 (unless it amounts

to more than 5 percent of the organization’s gross receipts or assets).

Many organizations fear news about employee theft could damage their reputations and make it harder to raise money from donors.

“Donors don’t want to be associated with anyone in the nonprofit world

who has a bad news cloud over their head,” said Tom McLaughlin, a

nonprofit consultant in Andover who has published several books on

financial management in the sector.

So nonprofits typically avoid publicity when they discover someone

pilfered funds. In some cases, nonprofits try to quietly negotiate

deals to have workers leave or repay the organizations instead of

reporting theft to police.

“I have had cases where they don’t want to prosecute,” said Janet

Fohrman, a certified fraud examiner and chief executive of Fohrman

& Fohrman, a nonprofit accounting firm in Laguna Hills, Calif.

“They just want to sweep it under the rug.”

And even when organizations go to police, it doesn’t always result in

criminal charges, because embezzlement cases can be difficult to

prosecute — especially when they involve organizations with messy

financial records or cash contributions that don’t leave a financial

trail.

Pantry

associate Marni Berliner worked at the Somerville Homeless Coalition’s

food pantry. Craig F. Walker Globe Staff

The Somerville Homeless Coalition said it quickly fired executive

Warren McManus after discovering the theft in November 2015. It also

sent a letter to donors in March 2016 and reported the incident to the

US Department of Housing and Urban Development, which supplies about

one-third of its funding.

“We recently discovered that one of our employees engaged in financial

misconduct that has led us to terminate his employment,” the group told

donors. “We at SHC were shocked and disappointed, to say the least, by

our former colleague’s breach of trust.”

A 2017 HUD report confirmed that independent auditors found funds were

misappropriated. HUD said it referred the matter to its Office of

Inspector General, which is charged with investigating fraud and

misconduct.

But no one has ever been prosecuted or publicly accused of the theft.

The group’s initial letter to donors did not include McManus’s name,

and it asked recipients to treat details confidentially. And it hasn’t

been previously mentioned in the media.

Indeed, the news was kept so quiet that the city of Cambridge passed a

glowing resolution praising McManus, five months after his firing, for

his years of service to young and disadvantaged people. Cambridge

officials said they weren’t aware of the embezzlement allegations at

the time.

Alston-Follansbee said he did not report the theft to Somerville Police

because an agent with HUD’s Office of Inspector General told him he was

handling the investigation and would notify other key officials. “I

would like to see this guy in jail,” Alston-Follansbee said. HUD’s

inspector general said it could not confirm or deny any investigatory

actions.

McManus, who now lives in upstate New York, initially hung up on a

reporter calling for comment. But he later called and e-mailed to

explain the situation after the Globe sent him a letter by certified

mail.

The 71-year-old said he handled the finances, purchases, and other key

duties for the organization for more than two decades. “I ran the

show,” he said.

McManus said he typically worked seven days a week and took only three

holidays a year. Instead of taking vacations, he said, he generally

paid himself extra for the time he had earned. But at some point, he

apparently lost track of his hours.

“The problem became that I took more vacation time than I earned,” McManus said.

McManus also acknowledged that he added his adult son to the agency’s

health insurance policy, even though Somerville Homeless said the son

was never eligible. “He is a bad diabetic, so I put him on for a short

time,” McManus said, adding that he later forgot to take him off the

policy. “It is entirely my fault,” he said.

McManus said he met with federal investigators last Thursday, signed a

statement concurring with several allegations, and agreed to pay back

$61,854. (It’s not clear why the figure is less than the $108,000

Somerville Homeless’s executive director estimated McManus owes.)

“I’ll own up to it,” McManus said. “I’ll make full restitution.”

Carolina Deleon comforted her daughter Jereiwi De Los Santos, 4, at the

Somerville Homeless Coalition Family Shelter, where they are guests.

But McManus said he hadn’t seen any allegations that he misused the

agency’s credit card, so he wasn’t sure whether those allegations were

correct.

And McManus said he feels the organization owes him as well. Shortly

before he was fired, he said, he submitted an invoice for more than

$50,000 for extra hours he worked. He said he got no response.

Meanwhile, Somerville Homeless said it has learned from the experience.

“We thought we had good controls and financial systems,” Alston-Follansbee said. “We found out we had neither.”

The organization has since replaced its auditors, hired additional

finance staff, spread out the financial responsibilities, and

implemented a new 150-page set of policies. It has also worked with HUD

to address any outstanding concerns.

Alston-Follansbee said many donors were understandably upset after they

learned about the embezzlement. But he said they have continued to

support the organization. The group ended last year with a small

surplus.

“People were angry, but they did not desert us,” he said. “We’re still here.”

Major nonprofit losses

More than 1,100 nonprofits told the IRS they suffered a significant,

unauthorized diversion of assets - usually theft or embezzlement - in

electronic filings processed between 2011 and 2017. The list is

incomplete for various reasons. The IRS asks the question on the

standard information return, called a 990, but not on versions filled

out by most private foundations or smaller organizations. Many

organizations still file paper forms. And the IRS requires

organizations to report thefts only of $250,000 or more, unless they

involve at least 5 percent of the group's income or assets.

top contents

appendix

previous next