Ride-hailing giant Didi Chuxing invests into bike-sharing startup

Shanghaiist

By Alex Linder

27 September 2016

After ruthlessly devouring Uber's operations in China, Didi Chuxing,

the country's top ride-hailing company, has moved on to its next target—bikes.

The company announced yesterday that it has invested "tens of millions

of dollars" into the bike-on-demand startup Ofo, which was launched on

the campus of Peking University as a student project back in 2014. The

two companies released a joint statement saying that they will

collaborate on product development, technology, data and business

operations.

While it's not clear what exactly that means, it's assumed

that Didi plans to help Ofo expand outside of college campuses by

eventually placing it on its own extraordinarily popular app.

Bike-on-demand services are becoming increasingly popular in China as

an alternative form of transportation that is more environmentally

friendly. In fact, Ofo currently has over 1.5 million users in 20

cities across China who take 500,000 bike rides per day.

Ofo isn't the

only app specializing in this competitive marketplace, but it is the

only one backed by Didi.

top

Xiamen completes world’s longest ‘cycling skyway’

Shanghaiist

By Alex Linder

24 January 2017

China has completed work on its first "cycling skyway." Surprise, surprise, it also happens to be the world's longest.

The 7.6-kilometer long "skyway" runs 5 meters above the road and just

below a bus rapid transit line in downtown Xiamen. It's targeted at

decreasing traffic congestion and promoting "green" forms of

transportation in the city.

Bicycles are once again becoming a more and more popular way of getting

around for China's urbanites thanks to the exploding popularity of a

few bike-sharing apps and the omnipresent traffic jams in Chinese

cities.

top

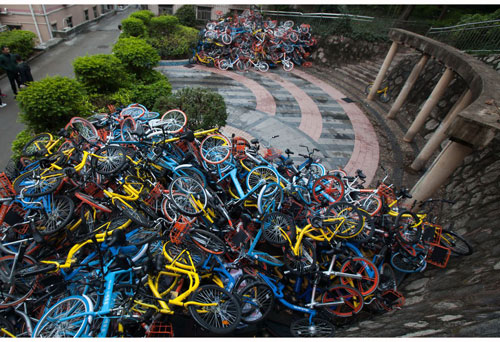

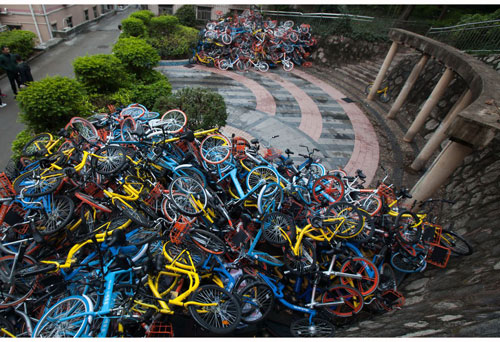

This is why there are huge piles of bikes in China

Wonderful Engineering

By Umer Sohail

21 January 2016

IMAGE: SILENT HILL/IMAGINE CHINA

IMAGE: SILENT HILL/IMAGINE CHINA

Bike sharing business is big in China, especially after the smog

concerns that have been haunting the citizens for quite some time. But

in China, bike-sharing providers don’t work like the ones at New York’s

Citi Bike. You don’t have to place the bike in a dock. Instead, you can

simply find one with your app, ride it, and leave it by the curbside

when you’re done.

vandalizing, destroying or dumping of these

bikes after use

While this may be more convenient, there is a significant downside to

it. The vandalizing, destroying or dumping of these bikes after use is

a serious emerging issue. People have been rather careless with the

usage; leaving the bikes on the sidewalks without realizing that they

are blocking the sidewalks, and even causing traffic hazards due to

their callous attitude.

These astonishing pictures of massive piles of bikes in Shenzhen say it

all, as several bike-sharing startups have launched a rather creative

protest against the malpractice, They have stacked hundreds and

thousands of bikes on the street corners in the hopes of raising

awareness about the criminal attitude by the users.

IMAGE: SILENT HILL/IMAGINE CHINA

Florian Bohnert, CEO of Mobike which is one of the bike providers, said

that the pile is created with the help of a condo facility’s management

personnel.

“The Shenzhen government is most proactive in supporting us…This kind

of behavior is isolated, but also criminal,” he said.

Nuisance caused by inconsiderate users, misuse, and theft, have been a

huge problem for the bike companies as well as the city administration,

who on Tuesday had to round-up bikes that were left by the streets and

walkways, blocking the sidewalks. The authorities also had to stop

selling the stolen bicycles from bike-sharing companies to minimize the

crisis, with many online marketplaces like Taobao also placing such

bans.

Social media has also been filled with people uploading pictures of

bikes thrown in the rivers or even up in trees.

IMAGE: SILENT HILL/IMAGINE CHINA

All these incidents have occurred even when the bikes from Mobike, ofo,

and Bluegogo are trackable through their GPS units. The companies do

take note of their inventory, including the bikes that get vandalized,

but they haven’t released any data on how many of them get destroyed

every year.

IMAGE: SILENT HILL/IMAGINE CHINA

And even though Mobike offers their users incentives like ride credits

for rescuing stranded bikes but the efforts to secure bikes are still

in vain.

top

China’s “Uber for bikes” startups are being taken for a ride by thieves, vandals, and cheapskates

Quartz

By: Echo Huang & Josh Horwitz

28 February 2017

Ofo and Mobike vehicles on the streets of Shanghai. (John Pasden/Flickr)

First it was the taxi-hailing wars. Then it was the on-demand service

wars. Now, China’s internet industry is watching another money-burning

battle unfold between rival startups.

Within the past year venture capital firms have poured hundreds of

millions of dollars into rival companies, all competing to become

China’s “Uber for bikes.” Their premise is simple: Pedestrians looking

for a lift can open their smartphones, unlock a bike parked nearby, hop

on for a ride, and pay a fee once they arrive at their destination.

It’s difficult to overstate how popular these services have become. On

almost every street corner in China’s major cities, bikes of different

shapes, sizes, and colors are lined up next to one another.

But widespread customer negligence and razor-thin margins could make it

hard for these businesses to stay afloat. The very factors that make

China’s bike-share services so convenient—low prices and ease-of-use,

namely—are the same factors that could spell their death.

“What they’ve got is a very interesting technology, but a basic

business model that makes no sense,” says Paul Gillis, who teaches

accounting at Peking University in Beijing.

Brakes off

Bike-sharing is not new, but Chinese startups have reinvented the concept to make it even more efficient.

Most bike-sharing schemes, like those in New York or Taipei, require

bikes to be parked into designated docks when not in use. There’s often

no way to know where these locations are, so riders have to plan out

their routes in advance. Or there might be a clunky app, perhaps from

the same government agency that funded the program.

China’s bike-sharing startups, on the other hand, allow their vehicles

to be placed anywhere in the city. Best-in-class engineers have

developed GPS-based apps that allow people to find nearby bikes, and

charge based on how much time riders spend on them.

Bullish venture capitalists funded rapid expansion, ensuring companies

have plenty of cash to buy bikes and put them on the streets. Prices

are dirt-cheap. After paying a small deposit through WeChat or Alipay,

two Chinese online payment services, 30 minutes on a bike will cost

between 0.5 and 1 yuan ($0.07 and $0.14), depending on the brand.

As a result, many Chinese have taken up bike-sharing as a replacement

for the subway, or even walking. Judy Zhao, a 25-year-old marketing

executive, tells Quartz that she takes the bus every day to work, but

as soon as she gets off at 5:30pm, she hops on a Mobike to cycle back

home.

“It’s about 20 minutes to ride [from my office to home], so I only need

to pay 0.5 yuan (about $0.07),” she tells Quartz. “It’s cheaper than

public transportation.”

Numerous companies have climbed onto the bike-sharing bandwagon, but

two startups lead the pack in terms of venture capital funding: Mobike

and Ofo.

Mobike, which was founded in late 2015 by a former Uber China employee,

first grew popular in Shanghai and is now in 23 cities across China.

Investors have funded it at lightning speed: It secured two venture

capital rounds this year alone that jointly totaled about $300 million.

Its backers include Singapore sovereign wealth fund Temasek, along with

Foxconn, the manufacturing giant best known for making the iPhone.

Chief rival Ofo was founded in late 2014. It grew popular on college

campuses in Beijing before raising $130 million last October from nine

investors including Xiaomi and Didi Chuxing, the ride-hailing giant

that acquired Uber’s China division. On March 1, it announced it closed

an additional round totalling $450 million.

Inspired by Ofo and Mobike’s swift uptake in early 2016, rival

companies followed suit and a mini-bubble surfaced. About 30

bike-sharing companies (link in Chinese) exist in China right now, with

many founded in 2016. Five of those companies went on to raise

double-digit funding by year’s end, according to Chinese tech database

IT Juzi.

Mobike spokesman Xue Huang says that several factors have helped make

China ripe for a bike-sharing boom. For one thing, most of the world’s

bikes are made in China, which means they can go directly from the

factory warehouse to the streets. Roads in China’s major cities tend to

be flat and wide, and populations are dense. Most important, unlike in

other parts of the world, riding bikes around in China never really

went out of fashion. Until only recently, it was the predominant mode

of urban transportation.

“China used to be a kingdom of bicycles. When I was young in the ’90s,

there were bikes everywhere,” says Huang. “And given the population is

already well-trained [to ride them], they’re just looking for something

more convenient.”

Riding on the honor system

While Mobike, Ofo, and their many rivals are easy to use, they’re

equally easy to abuse. The companies basically rest on the “honor

system,” and consumer negligence poses a serious threat to their

long-term viability.

The “park anywhere” policy is a blessing and a curse. On the one hand

it increases the likelihood that bikes will be found in one’s immediate

vicinity. But it also allows riders to park their bikes in remote

locations with no nearby foot-traffic. As a result, bikes parked along

freeways are now a common sight in China.

Property managers, meanwhile have started to complain about bikes

taking up space besides private buildings, or blocking pedestrians on

the sidewalk. News reports of bike-share vehicles piling up in

dumpsters, ditches, rivers, and even trees (link in Chinese) make

regular appearances on Chinese social media.

Bikes being piled up in Shenzhen's Xiashan Park on Jan. 16, 2017.

To manage this problem, Mobike and other companies rely on volunteer

users to spot and report discarded bikes. But they have also hired

in-house teams specifically for rounding up these dispersed bikes, and

taking them to high-traffic hubs or repair centers. That costs money.

Uber and Didi don’t have to deal with this problem, since those

companies generally don’t own the cars connected to their apps.

Then there’s the problem of theft and vandalism. Mobike vehicles lock

and unlock when a rider scans the QR code attached to a bike. But many

people—perhaps employees at competing companies—will deface these QR

codes, rendering the bikes unusable.

The QR code that use to unlock the bikes are scratched sometimes.

Ofo bikes, meanwhile, unlock when a user scans the bike plate, receives

a four-digit password via smartphone, and then inputs the code into an

old-fashioned mechanical lock. But these mechanical locks have

permanent passwords. Users can simply memorize the password of a

particular bike, unlock the mechanical lock, and re-secure it using

their own personal lock. This lets users effectively steal the bike

after first use, and ride it without being bound to the app’s timer.

Recently, two nurses in Beijing spent five days in jail after they were

caught using this trick on Ofo’s bikes—though most such riders probably

go about unnoticed.

Potholes ahead

All of these factors merely compound the stress placed on an already

shaky business model. Mobike and its rivals won’t reveal how much their

bikes cost to produce, but an old estimate (which Mobike says has since

decreased) places the cost of a standard Mobike at 3,000 yuan (about

$437). Professor Gillis says that fares alone will hardly recoup these

costs in a timely manner—let alone cover labor and R&D expenses.

“They rent for one yuan every half hour, and they expect that they

might be rented four times a day for a half hour, which amounts to four

yuan per day,” he tells Quartz. “If you take four yuan per day and you

take that into the 3,000 yuan, you’ve got a long time before you’ve

recovered the cost of a bike.”

Profit-challenged Chinese internet companies have a habit of living

long lives once they get big, especially if a larger internet company

like Alibaba or Tencent acquires them. Mobike and Ofo have a lot going

for them. Like Uber and Didi, they collect lots of data about traffic.

More important, they align well with the central government’s

commitment to reducing pollution nationwide, as well as its ambition to

promote itself as a global innovator in technology.

The government won’t necessarily stay a friend for long. It’s already

begun to turn its back on Didi Chuxing, for instance, by issuing new

restrictions on driver eligibility, cutting the supply and making it

harder for customers to hail a ride. If Mobike and its rivals can find

a suitor quickly, they can perhaps live on comfortably as a loss leader

for a deep-pocketed parent company. But if not, or if the government

decides their popularity is chipping away at buses and subways, many of

the bikes lining China’s street corners might soon end up in the

junkyard—or wherever.

top contents

chapter

previous

next

IMAGE: SILENT HILL/IMAGINE CHINA

IMAGE: SILENT HILL/IMAGINE CHINA