The government says it has a plan to fix the housing affordability crisis. This chart suggests it doesn't

The Sydney Morning Herald

Inga Ting

05 September 2016

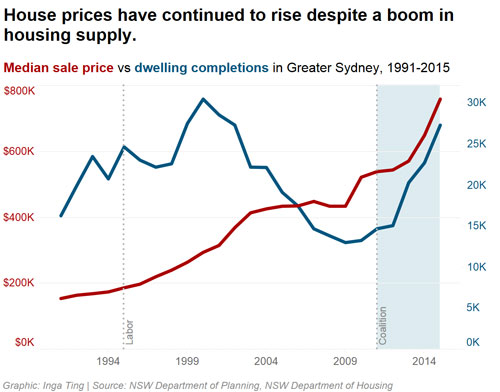

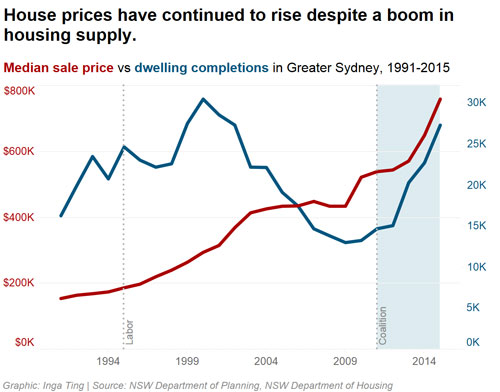

This is the chart economists say demonstrates that the government's plan to halt rocketing house prices is doomed.

It shows house prices in Greater Sydney have continued to climb skyward despite a five-year boom in housing supply.

The NSW government insists change is on the horizon. Housing

completions are only now recovering from a seven-year slump and we will

see results in the next few years, according to the latest NSW

Intergenerational Report.

But economists, urban planners and community groups disagree, and this

week wrote an open letter urging the government to go beyond supply as

its sole strategy for moderating house prices. It is the first time

property developers, non-profit organisations, the finance sector and

universities have united to call for action on affordable housing.

Boosting supply

Since winning government in 2011, the Coalition's housing affordability

policy has rested on a seductively simple strategy: build more houses.

"The most effective way we can tackle housing affordability is to

increase supply," NSW Treasurer Gladys Berejiklian has said on numerous

occasions, including in a statement to Fairfax Media this week.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has backed the strategy, saying in May:

"Now this is how you address housing affordability. Housing

affordability is the result of there being insufficient supply of

housing. You need to have more supply of housing."

The economics seems basic enough: when supply goes up, price comes

down. Yet house prices have risen by 40 per cent since 2011 while

dwelling completions have ballooned by 85 per cent.

Houses are not bananas

"If they understood how housing markets actually worked, this would

come as no surprise at all," said Bill Randolph, director of UNSW's

City Futures Research Centre.

"The problem is you can't apply year 10 economic theory to a metropolitan housing market."

Homes are unaffordable not because we are building too few but because the market is flooded with cheap credit.

—Tim Williams, Committee for Sydney

The housing market doesn't behave like the market for bananas or cans

of beans, experts say. For example, when the price of bananas rise,

people buy fewer bananas and more alternative fruits, like apples or

oranges, said economist and geographer Peter Phibbs. Professor Phibbs

is chair of urban and regional planning and policy at the University of

Sydney, and director of the university's town planning innovation

centre, the Henry Halloran Trust.

"But with housing, because it's an asset market, as the price goes up

it encourages buyers to get into the market because they can see the

potential gain of holding an asset that's going up in value," Professor

Phibbs said.

This is particularly true in Australia because we have tax incentives

(namely, negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount) that

actively encourage investment in the private housing market, he said.

We just can't build that many houses

"Supply is incredibly important and it's very good it's been going up -

the population is growing; we need more houses," Professor Phibbs said.

But boosting supply alone won't put home ownership within reach of low and moderate income earners, he says.

The link between new supply and house prices is weak, economists argue.

It's not like the banana market, for example, where the entire supply

is produced each year and new supply has a strong link to price. In the

housing market new homes are a tiny fraction of the entire housing

supply.

"Nobody has ever shown … that you can supply enough housing into a

market to effectively make prices fall," Professor Randolph said.

"New supply is 2 per cent of the housing market. Even if that doubled,

what impact would that have? Most of us buy second-hand housing."

Making matters worse in Australia is a finance model that essentially

ties supply to demand by requiring developers to sell a certain

proportion of new housing off-the-plan, Professor Phibbs said.

"It's unlikely that additional supply will lead to sharp reductions in

price because the stock has already been sold … Supply never gets very

far in front of demand," he said.

The price of money

But there is a more fundamental reason the relationship between house

prices and supply is not simple or straightforward, according to

planning expert and Committee for Sydney CEO Tim Williams.

In the housing market, 'demand' is not driven by housing 'need' but by

access to housing finance, he says. Virtually everyone needs to borrow

money to buy a home, which means the major determinant of house prices

is the price of money itself.

"Homes are unaffordable not because we are building too few but because the market is flooded with cheap credit," he said.

"Increasingly access to this is being channelled to existing homeowners

over first-time buyers, leading to many Sydneysiders owning two and

three properties while the average 30-year-old cannot get into home

ownership.

"We cannot build our way to affordability in such a market."

What should we do?

Asked whether the government should consider strategies other than

boosting supply, Ms Berejiklian said again that increasing supply was

"the most effective way of tackling housing affordability".

"When we came to office in 2011, NSW annual residential construction

spending was just $12.4 billion and building approvals were below

35,000," she told Fairfax Media.

"NSW building approvals have more than doubled to over 70,000 and real

residential construction over the past year has reached $19.4 billion –

the highest level on record."

Professor Phibbs advocates inclusionary zoning, which would require new

developments to include a certain number of homes for moderate- and

low-income earners.

"It's been used in a lot of American cities," he said. "You can't use

it everywhere but in high-value areas it's really a no-brainer."

Professor Randolph suggests encouraging investment in properties for

long-term rent. This would divert demand from the housing market and

provide "a real alternative to the nightmare of current private

rental," he said.

And there's always tax reform, although he acknowledges the lack of political appetite.

Ultimately, we need to reset some entrenched ideas about how we provide housing, Professor Randolph said.

"It is a wicked problem," he said. "That's why most of our governments just rub their heads and walk away."

top

contents

appendix

previous next